The Eurasian Consolidation (2026)

From Pipeline Politics to War Economy: Competitive Coordination and Its Limits

The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the subsequent Western sanctions regime accelerated processes that had been developing for decades: the reorientation of Russian energy and commodities toward Asian markets, the construction of infrastructure bypassing Western-controlled transit routes, and the diplomatic alignment of states excluded from or marginal to the American-led order. The "turn to the East" that Russian policy documents had long advocated became material necessity. The "no limits partnership" between Russia and China, declared shortly before the invasion, was tested and deepened by shared confrontation with Western sanctions. The expansion of BRICS in 2024, incorporating Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Ethiopia, provided institutional framework for this reorientation, however limited its operational capacity. What emerged was less a planned new order than a siege economy—a hastily assembled network of alternative routes and mechanisms defined as much by what it excludes (Western control) as by what it integrates.

The question that follows is whether this acceleration constitutes qualitative transformation—the emergence of Eurasian bloc capable of challenging Western hegemony—or quantitative intensification of patterns that remain constrained by structural obstacles. The analysis examines the institutional and infrastructural architecture of attempted consolidation: energy and commodity flows, financial mechanisms, military cooperation, and the diplomatic frameworks that coordinate without integrating. The assessment is skeptical: the Eurasian powers face competitive interests that preclude genuine alliance, structural dependencies that Western sanctions have intensified rather than eliminated, and the temporal contradiction that their cooperation attempts to address—relative decline of American hegemony—generates pressures that undermine their own capacity for collective action.

The Material Base: Energy, Commodities, and Infrastructure

The foundation of Eurasian consolidation is material: the hydrocarbon reserves of Russia, Iran, and Central Asia; the mineral resources of Siberia and the Arctic; the agricultural production of Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan; the industrial capacity of China and, to lesser extent, India. The complementarity is apparent: energy and raw materials flow eastward, manufactured goods flow westward, with infrastructure construction—pipelines, railways, ports—enabling circulation that maritime Western dominance had constrained.

The Power of Siberia pipeline, operational since 2019, delivers Russian gas to China; Power of Siberia 2, under negotiation, would expand capacity and connect western Siberian fields. The Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline enables Russian crude export to Asia independent of European transit. These projects, long delayed by pricing disputes and Chinese reluctance to over-depend on single supplier, were accelerated by Western sanctions that eliminated European alternative. The "strategic partnership" became material necessity for Russia and commercial opportunity for China.

The Iranian dimension adds further complexity. Sanctioned by Western powers since 1979, Iran developed infrastructure and trading relationships oriented toward Asia: oil sales to China and India, barter arrangements, financial mechanisms bypassing dollar clearing. The 25-year comprehensive cooperation agreement with China, signed in 2021, provides framework for expanded investment, though implementation has been slower than announced. The normalization of Saudi-Iranian relations, brokered by China in 2023, reduced Gulf tensions that had constrained regional energy cooperation, though it did not eliminate competitive dynamics.

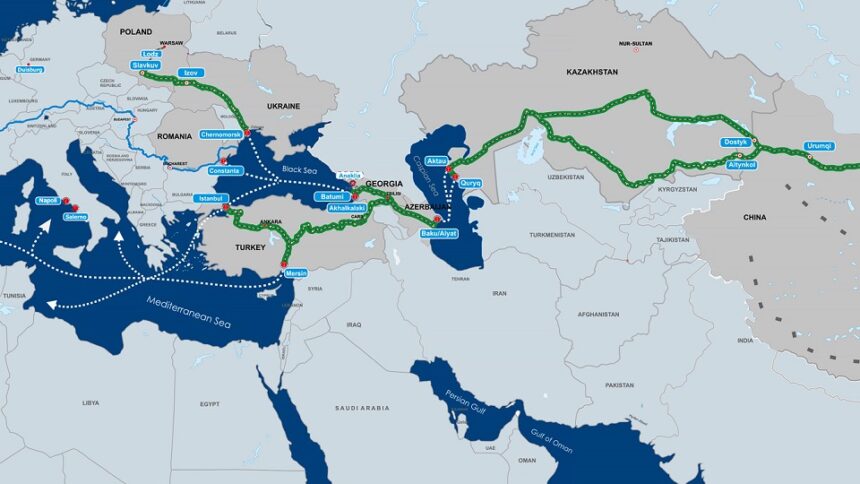

The infrastructure of Eurasian consolidation extends beyond energy to transportation and digital connectivity. The International North-South Transport Corridor—envisioned since 2002, operationalized since 2022—connects Russia through the Caucasus and Caspian to Iran and Indian Ocean ports, reducing transit time and cost compared to Suez Canal routes. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor provides alternative Indian Ocean access bypassing Malacca Strait chokepoint. The Northern Sea Route, opened by climate change and developed by Russian investment, offers shorter Europe-Asia transit that remains ice-limited and militarily vulnerable.

The digital infrastructure is similarly contested: Chinese Huawei 5G networks in Central Asia and Russia, Russian GLONASS and Chinese BeiDou navigation systems, national internet infrastructures with varying degrees of Western platform exclusion. The "cyber-sovereignty" that Eurasian states claim involves not merely protection from Western surveillance but construction of alternative networks that Chinese technology dominates.

The Financial Architecture: De-dollarization and Its Limits

The sanctions weaponization of dollar-based financial infrastructure—SWIFT exclusion, frozen reserves, secondary sanctions—generated accelerated efforts toward alternative arrangements. The bilateral currency swaps between China and trading partners, the Russian SPFS and Chinese CIPS messaging systems, the exploration of central bank digital currencies, and the commodity pricing in national currencies—all represent attempts to reduce dollar dependency that Western policy has intensified.

The achievements are real but limited. Bilateral trade between China and Russia is substantially conducted in yuan and rubles; India purchases Russian oil in rupees; Iran has long experience with sanctions-evading financial mechanisms. But the dollar remains dominant in global trade, in foreign exchange reserves, in commodity pricing. The alternative systems lack depth, liquidity, and trust; they function for specific transactions but cannot replicate the dollar's universal intermediation. The "de-dollarization" that BRICS rhetoric proclaims is aspiration rather than achievement, and the structural obstacles—network effects, institutional inertia, absence of credible alternative—are formidable.

The financial integration of Eurasian economies is further constrained by competitive dynamics. China's financial system is state-controlled and capital-account restricted; Russia's has been partially liberalized and then re-constrained by sanctions; India's remains domestically oriented with limited convertibility. The "multipolar" financial order that is envisioned would require coordination that competitive nationalism prevents: shared reserve currency, integrated banking supervision, common crisis response mechanisms. The BRICS New Development Bank and Contingent Reserve Arrangement, established 2014-2016, remain marginal to global financial governance, their capitalization inadequate to systemic challenges.

The temporal dimension compounds these constraints. Dollar-based financial infrastructure was constructed over decades, with institutional embedding that transformation cannot achieve quickly. The urgency that sanctions generated—immediate need for payment mechanisms, reserve security, investment channels—produced workarounds rather than alternatives, temporary adaptations that do not cumulate into systemic replacement. The "transition" to multipolar finance, if it occurs, will extend across decades that geopolitical competition may not permit. Thus, the financial 'decoupling' remains a patchwork of workarounds, while the more profound technological decoupling—in semiconductors, AI, and advanced manufacturing—proves a harder, slower frontier, exposing the fundamental dependency that underpins the rhetoric of autonomy.

The Ideology of Multipolarity: Sovereignty as a Strategic Weapon

Beneath the material competition lies a battle of narratives. The "civilizational" and "multipolar" discourse promoted by Moscow and Beijing is a potent soft-power tool that resonates across the Global South, weaponizing post-colonial grievances to frame Western hegemony as the singular source of instability. The vocabulary of "sovereignty," "non-interference," and "civilizational diversity" provides a coherent ideological counter to liberal interventionism, offering a principled rationale for what is often pure realpolitik. Yet this ideology masks the neo-imperial nature of their own economic and security projects within Eurasia itself. It functions as strategic weapon: delegitimizing Western pressure while legitimizing their own spheres of influence, creating a diplomatic shield that makes containment politically costly.

Military Cooperation: Alignment Without Alliance

The military dimension of Eurasian consolidation is characterized by alignment without alliance: coordination against shared adversary without integrated command, equipment standardization, or mutual security guarantees. The Russia-China relationship is most developed: joint exercises, technology transfer, intelligence sharing, and diplomatic coordination. But the "no limits partnership" explicitly excludes formal alliance; Chinese officials emphasize that relationship "is not targeted at any third party," maintaining ambiguity that preserves flexibility.

The military-technical cooperation is substantial but asymmetrical. Russia supplies China with advanced weapons systems—S-400 air defense, Su-35 aircraft—that Chinese industry subsequently reverse-engineers and replaces with domestic alternatives. The Ukraine war has accelerated this dynamic: Russian military equipment has proven inadequate against NATO-supplied Ukrainian forces, reducing the attractiveness of Russian arms exports; Chinese observation of Russian operational difficulties informs its own military modernization without requiring replication of Russian errors. The "partnership" involves learning from Russian failure as much as benefiting from Russian capability.

The Iranian dimension adds further complexity. Military cooperation with Russia—drone technology transfer, satellite launch assistance, potential missile technology—has developed since 2022, but remains constrained by Iranian strategic autonomy and Russian reluctance to provide systems that might provoke Israeli or American response. The "axis of resistance" that Iran constructs—Hezbollah, Hamas, Houthis, Iraqi militias—serves Iranian regional interests that do not necessarily coincide with Russian or Chinese priorities. The Gaza war of 2023-2024 demonstrated both coordination (Iranian-supported forces pressuring Israel on multiple fronts) and limitation (no direct Iranian intervention, Russian and Chinese diplomatic caution).

The Indian position is most ambiguous. Historical Russian arms supply and strategic partnership—formalized in 1971 treaty, continued despite Western pressure—coexists with Quad alignment with United States, Japan, and Australia; border confrontation with China that produced lethal clashes in 2020; and aspiration to strategic autonomy that rejects formal alliance with either bloc. Indian participation in BRICS and SCO serves multiple purposes: managing Russia relationship, constraining Chinese dominance, accessing alternative institutions without excluding Western partnership. The "multi-alignment" that Indian strategists claim is not Eurasian consolidation but its complication.

The Institutional Framework: BRICS, SCO, and Forum Diplomacy

The institutional architecture of Eurasian consolidation is characterized by proliferation without integration: multiple forums with overlapping membership, competing agendas, and limited operational capacity. BRICS provides the most prominent framework—expanded 2024 to include major energy exporters and African economies—but remains essentially consultative, its declarations aspirational, its mechanisms underdeveloped. The New Development Bank, BRICS's most concrete achievement, lends at modest scale compared to Bretton Woods institutions, with governance and currency arrangements that do not challenge established order.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) includes Russia, China, Central Asian states, India, Pakistan, and Iran, with observer and dialogue partner status for additional states. Its security dimension—counter-terrorism cooperation, intelligence sharing, military exercises—addresses shared concerns about separatism and instability, but does not extend to collective defense or integrated command. The economic dimension—trade facilitation, investment promotion—remains underdeveloped compared to bilateral arrangements. The SCO functions primarily as forum for regional dialogue and bilateral deal-making rather than as cohesive bloc.

The Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), Russian-led and Central Asian-focused, has achieved modest trade integration but remains dominated by Russian economy and constrained by Chinese Belt and Road investments that bypass or compete with EEU mechanisms. The "Greater Eurasian Partnership" that Russia has proposed would integrate EEU with Chinese Belt and Road, but implementation has been slow and Chinese investment in Central Asia proceeds through bilateral channels rather than multilateral frameworks.

The institutional fragmentation reflects competitive interests that formal integration would require resolving. China prefers bilateral arrangements that maximize its leverage; Russia seeks multilateral frameworks that constrain Chinese dominance and preserve its own influence; India participates without committing; Iran is constrained by sanctions and regional isolation; Central Asian states balance multiple relationships without exclusive alignment. The "multipolarity" that these institutions claim to represent is less coordinated challenge to Western hegemony than competitive positioning within emerging order that none can dominate.

The Obstacles: Competitive Nationalism and Structural Dependency

The fundamental obstacle to Eurasian consolidation is competitive nationalism: the pursuit of national interest that cooperation would require subordinating to collective framework. Russia and China are strategic partners but also historical rivals, with territorial disputes resolved but not forgotten, with competing influence in Central Asia, with divergent interests in Arctic, Pacific, and Indian Ocean regions. The "no limits partnership" explicitly maintains limits: no formal alliance, no integrated military command, no shared nuclear umbrella, no common market with free movement.

The economic asymmetry between China and other Eurasian powers compounds competitive dynamics. Chinese economy is larger than all other BRICS combined; its manufacturing capacity exceeds global demand in multiple sectors; its Belt and Road investments create debt dependencies that recipient states resent. The "win-win" rhetoric of Chinese diplomacy masks structural extraction: raw materials and energy flow to China, manufactured goods flow outward, with technology transfer and value-added production concentrated in China. The "development" that Chinese investment enables is subordinate insertion into Chinese supply chains rather than autonomous industrialization.

The structural dependencies that Western sanctions intensified rather than eliminated constrain Eurasian autonomy. Russian military equipment depends upon Western-origin semiconductors and components that sanctions restrict and covert procurement cannot fully replace. Chinese advanced manufacturing depends upon Taiwan Semiconductor and Dutch ASML equipment that export controls constrain. Iranian economy depends upon oil export that sanctions restrict and smuggling cannot fully compensate. The "decoupling" that Western policy pursues is partial and asymmetric; the "self-reliance" that Eurasian states claim remains aspiration rather than achievement.

The temporal contradiction is decisive: the relative decline of American hegemony that creates space for Eurasian consolidation also generates pressures that undermine it. The urgency of immediate confrontation—sanctions evasion, military procurement, diplomatic coordination—takes priority over long-term institution-building. The competitive dynamics that American decline enables—Chinese assertion, Russian desperation, Indian multi-alignment, Iranian regional ambition—generate conflict that consolidation would require managing. The "strategic patience" that successful consolidation would require is incompatible with the crisis tempo that decline generates.

The War Economy Dimension: Ukraine and the Siege Economy Forged in Conflict

The Ukraine war has transformed Eurasian consolidation from diplomatic possibility to material necessity for Russia, and from commercial opportunity to strategic risk for China. The Russian economy's conversion to war footing—state-directed production, labor mobilization, import substitution—has achieved surprising resilience but at cost of technological regression and long-term growth sacrifice. This militarized mobilization creates new, hardened facts on the ground: supply chains for drones, artillery, and ammunition now snake through North Korea and Iran, creating dependencies and relationships that outlive specific conflicts. The "military Keynesianism" that sustains employment and production is not sustainable development but the core logic of the siege economy.

The Chinese response has been calibrated support without full commitment: expanded energy and commodity purchases, financial mechanisms bypassing sanctions, diplomatic protection at United Nations, but no military equipment supply that would trigger secondary sanctions and jeopardize Western market access. The "no limits partnership" has proven to have limits: Chinese banks restrict transactions with sanctioned Russian entities; Chinese technology exports comply with American export controls; Chinese diplomacy maintains Western relationships alongside Russian partnership.

The architecture of this siege economy relies on critical intermediaries. Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have become indispensable financial and logistical hubs, leveraging their non-aligned status to facilitate trade, finance, and technology flows that formal channels block. Their power derives not from military might but from their role as the pressure valves and backchannels of the sanctioned economy, making them both essential and perpetually vulnerable to the shifting whims of greater powers.

The spillover effects extend across Eurasia. Central Asian states—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, others—have exploited Russian distraction to assert autonomy, resisting integration initiatives that would subordinate them to Russian-led frameworks. The Caucasus—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia—has seen intensified conflict and great power competition that Russian hegemony had suppressed. The Middle East—Syria, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel—has experienced realignment and conflict that Russian and Chinese influence cannot stabilize. The "consolidation" that Ukraine was supposed to accelerate has generated fragmentation that it cannot control.

The Global South in the Interregnum: Playing the Field

This competitive coordination has unlocked agency for states across Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Rather than passive recipients of a new bipolarity, these states are actively exploiting the interregnum to play powers off each other—securing investment from China while buying discounted oil from Russia, acquiring arms from multiple suppliers, and using BRICS membership to extract concessions from Western institutions. This is not a story of the Global South aligning with a Eurasian bloc, but of its political elites skillfully navigating the fragmentation of hegemonic power to maximize their own bargaining position, often at the expense of their own populations' sovereignty and development.

Conclusion: Competitive Coordination and the Interregnum

The Eurasian consolidation that policy discourse and some analysis identifies is more accurately described as competitive coordination: alignment against shared adversary without integration into cohesive bloc, cooperation in specific domains without collective framework, diplomatic coordination without mutual commitment. The structural obstacles—competitive nationalism, economic asymmetry, structural dependency, temporal contradiction—are not temporary but constitutive. The "multipolarity" that this coordination claims to represent is less new order than extended interregnum: period of American relative decline without successor hegemony, of institutional fragmentation without alternative construction.

The question for analysis is whether this interregnum can be extended indefinitely, or whether competitive pressures generate confrontation that forces alignment into alliance or dissolution. The Ukraine war has demonstrated both the possibilities and limits of Eurasian coordination: Russian resilience with Chinese support, but also Chinese restraint and Russian isolation. The Taiwan scenario—potential confrontation that would test China-Russia partnership more severely—remains speculative but instructive: Chinese priority for reunification, Russian interest in Western distraction, but also risk of escalation that neither can control and that would expose the limits of their partnership.

The alternative—genuine Eurasian integration with common market, collective security, and shared institutions—would require transformation of national interests that competitive nationalism prevents. The "civilizational" framing that some Russian and Chinese discourse proposes—Eurasia as alternative to Atlantic West—masks national interests that such framing would require subordinating. The historical precedent—Soviet-Chinese alliance and its dissolution—indicates the fragility of partnerships between communist states with even nominal ideological solidarity; the contemporary partnership lacks even this.

For the states of Eurasia, the interregnum presents opportunities and risks that competitive coordination attempts to navigate. For the global South, the proliferation of forums and partnerships offers leverage that non-alignment previously provided, but also risks of subordination to new hegemons. For Western powers, the consolidation that is feared is less developed than policy response assumes, but the competitive coordination that exists is sufficient to complicate containment strategy. The Eurasian project, therefore, is the geopolitical expression of the interregnum: a fragmented, reactive, and often contradictory coordination that can destabilize the old order but cannot birth a stable new one. It ensures the transition will be defined not by hegemonic succession, but by prolonged, competitive crisis-management—a permanent state of emergency masquerading as a new world order.

References

Organized by Analytical Themes

The Siege Economy and Sanctions Evasion

Claim: Western sanctions accelerated the construction of alternative routes and mechanisms defined by exclusion of Western control rather than positive integration.

Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis — Analyze trade imbalances and the global savings glut. See Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace (2020).

Adam Tooze — Documents the weaponization of financial infrastructure and sanctions regime. See Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World's Economy (2021) and subsequent analysis of Russia sanctions.

Nicholas Mulder — Examines the history and political economy of economic sanctions. See The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War (2022).

Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman — Analyze "weaponized interdependence" and network power. See "Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion" (2019) and subsequent work.

Michael Hudson — Analyzes how financial sanctions accelerate the search for alternatives and the construction of parallel systems. His work on the "tribute economy" and the weaponization of dollar hegemony informs understanding of the siege economy dynamic.

Energy Infrastructure and Pipeline Politics

Claim: Energy flows and infrastructure construction enable Eurasian circulation but create dependencies and pricing disputes.

Thane Gustafson — Examines Russian energy politics and the "turn to the East." See The Bridge: Natural Gas in a Redivided Europe (2020) and Klimat: Russia in the Age of Climate Change (2021).

Morena Skalamera — Analyzes Russia-China energy relations. See "The Russia-China Gas Deal: Shifting the Balance" (2014) and subsequent work at Harvard Davis Center.

Keun-Wook Paik — Documents Sino-Russian oil and gas pipeline development. See Sino-Russian Oil and Gas Cooperation: The Reality and Implications (2012).

Robert Cutler — Examines Eurasian energy infrastructure and geopolitics. See work at Carleton University and Energy Security Research.

Financial De-dollarization and Its Limits

Claim: Alternative financial mechanisms function as workarounds rather than systemic alternatives to dollar dominance.

Eswar Prasad — Analyzes the dollar's enduring dominance and challenges to it. See The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance (2014) and The Future of Money: How the Digital Revolution Is Transforming Currencies and Finance (2021).

Barry Eichengreen — Examines international currency competition. See Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System (2011) and How Global Currencies Work: Past, Present, and Future (2017, with Arnaud Mehl and Livia Chițu).

Jonathan Kirshner — Analyzes the political economy of currency power. See Currency and Coercion: The Political Economy of International Monetary Power (1995) and American Power after the Financial Crisis (2014).

Zongyuan Zoe Liu — Examines China's international financial architecture. See Sovereign Funds: How the Communist Party of China Finances Its Global Ambitions (2022).

Michael Hudson — Documents the construction and weaponization of dollar-based financial infrastructure. See Super Imperialism: The Economic Strategy of American Empire (1972, updated 2003) and Global Fracture: The New International Economic Order (1977, updated 2005). His analysis of how financial systems create dependencies informs understanding of de-dollarization limits.

The Ideology of Multipolarity and Sovereignty

Claim: "Multipolar" discourse weaponizes post-colonial grievances while masking neo-imperial projects.

Samuel Moyn — Analyzes "humane" imperialism and its critics. See Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War (2021) and work on international law and empire.

Adom Getachew — Examines post-colonial internationalism and its limits. See Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (2019).

Vijay Prashad — Documents the "darker nations" and Global South politics. See The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World (2007) and The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South (2012).

Oliver Stuenkel — Analyzes BRICS and post-Western global governance. See The BRICS and the Future of Global Order (2015) and BRICS: A Guide for the Perplexed (2024).

Michael Hudson — Analyzes how ideological framing of "sovereignty" and "development" obscures structural extraction. His critique of the "Washington Consensus" and its alternatives informs understanding of multipolarity ideology.

Military Alignment Without Alliance

Claim: Russia-China military cooperation lacks formal alliance structures and is characterized by asymmetry and learning from failure.

Yu Bin — Examines Sino-Russian military relations. See "In Search for a Normal Relationship: China and Russia into the 21st Century" and work at Wittenberg University.

Richard Weitz — Analyzes China-Russia security cooperation. See work at Hudson Institute and "Why Russia and China Have Not Formed an Anti-NATO Alliance" (2020).

Michael Kofman — Documents Russian military performance and Chinese observation. See work at CNA and War on the Rocks on Ukraine and Sino-Russian relations.

Paul J. Bolt and Sharyl N. Cross — Examine China-Russia strategic partnership. See Neither Friend nor Foe: China, Russia, and the Future of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (2018).

Institutional Fragmentation and Forum Diplomacy

Claim: BRICS, SCO, and EEU proliferate without achieving genuine integration due to competitive interests.

Alexander Cooley — Analyzes Central Asian regimes and great power competition. See Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia (2012) and Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (2020, with Daniel H. Nexon).

Marlene Laruelle — Examines Russia's Eurasian integration projects. See Russia's Eurasian Integration: Beyond the Post-Soviet Space (2015) and Is Russia Fascist? Unraveling Propaganda East and West (2022).

Thomas Fingar — Analyzes China's approach to global governance. See The New Great Game: China and South and Central Asia in the Era of Reform (2016, edited).

Sumit Ganguly and Manjeet S. Pardesi — Examine India's multi-alignment strategy. See "India and the Great Powers: Strategic Alignment, Structural Constraints" (2009) and subsequent work.

Competitive Nationalism and Structural Dependency

Claim: National interests and asymmetrical dependencies prevent genuine Eurasian integration.

Giovanni Arrighi — Analyzes systemic cycles of accumulation and hegemonic transition. See The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (1994) and Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (2007).

Branko Milanović — Examines global inequality and the "trilemma" of globalization. See Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (2016) and Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World (2019).

Dani Rodrik — Analyzes the "political trilemma of the world economy." See The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy (2011).

Kalpana Wilson — Examines race, gender, and neoliberal development. See Race, Racism and Development: Interrogating History, Discourse and Practice (2012).

Michael Hudson — Documents how structural dependencies—debt, technology, finance—constrain nominal sovereignty. His analysis of how "independence" is compatible with subordination informs understanding of competitive nationalism limits.

War Economy and Militarized Mobilization

Claim: Russian conversion to war footing creates siege economy logic and new dependencies that outlive specific conflicts.

Janine R. Wedel — Analyzes "flex organizing" and post-Soviet state transformation. See Collision and Collusion: The Strange Case of Western Aid to Eastern Europe (2001) and Shadow Elite: How the World's New Power Brokers Undermine Democracy, Government, and the Free Market (2009).

Chris Miller — Examines Russian economic policy and war mobilization. See Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia (2018) and subsequent analysis of sanctions and adaptation.

Richard Connolly — Analyzes Russia's political economy. See Russia's Response to Sanctions: How Western Economic Statecraft Is Reshaping Political Economy in Russia (2018).

Timothy Snyder — Documents Russian imperial politics and Ukrainian resistance. See The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America (2018) and On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (2017).

The Global South and Interregnum Agency

Claim: States across Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia exploit fragmentation to maximize bargaining position.

Christopher S. Browning — Analyzes "hedging" and non-alignment strategies. See "The Geopolitics of Hedging: Great Power Rivalry and the Sources of Hedging" (2022).

Amitav Acharya — Examines "multiplex" world order and Global South agency. See The End of American World Order (2014) and Constructing Global Order: Agency and Change in World Politics (2018).

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni — Analyzes decoloniality and Global South politics. See The Ndebele Nation: Reflections on Hegemony, Memory and Historiography (2009) and work on decolonial international relations.

Kelebogile Zvobgo and Meredith Loken — Examine race, gender, and international relations. See "Why Race Matters in International Relations" (2020).

Intellectual Tradition and Overall Framing

The text's overarching framework is most directly informed by:

Immanuel Wallerstein (World-Systems Analysis) — The concepts of hegemonic cycles, core-periphery relations, and the interregnum between orders. See The Modern World-System (4 vols., 1974-2011).

Giovanni Arrighi — The analysis of systemic cycles of accumulation and the "terminal crisis" of American hegemony. See The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (1994).

Carl Schmitt (critically appropriated) — The concept of "Nomos" and spatial ordering. See The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum (1950).

Mackinder and Spykman (critically appropriated) — The "Heartland" theory and rimland geopolitics. See Halford Mackinder, "The Geographical Pivot of History" (1904) and Nicholas Spykman, The Geography of the Peace (1944).

Michael Hudson — Synthesizes classical political economy and contemporary finance to analyze the dynamics of hegemonic transition, the weaponization of economic infrastructure, and the construction of alternative systems. His work on the "tribute economy," super imperialism, and the impossibility of reform within financialized structures provides essential grounding for the text's assessment of Eurasian consolidation as competitive coordination within interregnum rather than genuine alternative order. His analysis of how declining hegemons generate pressures that undermine successor coordination informs the temporal contradiction thesis.

Wolfgang Streeck — The analysis of capitalist decomposition and the exhaustion of institutional stabilization. See How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System (2016).

Antonio Gramsci — The analysis of "interregnum" and crisis of authority. See Selections from the Prison Notebooks (1929-1935, edited and translated 1971).

Fernand Braudel — The analysis of long-term structural trends and the "longue durée." See Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century (3 vols., 1979).

Want to stay informed about global economic

trends?

Subscribe to our newsletter for weekly analysis and insights

on international politics and economics.