The Digital Battlefield: Sovereignty, War, and the New Anarchy (2026)

How States Weaponize Platform Infrastructure to Dismantle Other States

Introduction: The Digital State of Nature

The preceding analysis examined how platform capitalism dismantles psychological capacity from within—the subjective colonization of consciousness that renders populations incapable of sustained political deliberation. This sequel examines the corollary process: how states weaponize the same infrastructure to dismantle adversaries from without. The relationship is not merely parallel but constitutive. The internal fragility of platform subjects and the external vulnerability of platform-dependent states are two faces of the same historical process. The cognitive twitchiness, affective dysregulation, and temporal disorientation that platforms induce in individuals become strategic assets when exploited by state actors; the platform epistemology that disables critical thought domestically becomes a delivery system for deception and demoralization internationally.

In the 21st century, a state that does not control its digital territory does not fully exist. The classical prerogatives of sovereignty—territorial integrity, monopoly on legitimate violence, monetary autonomy, capacity for collective self-determination—have all become dependent on control over information infrastructure. The "sovereign internet" is not an authoritarian eccentricity but the necessary adaptation of the Westphalian state to a domain that threatens to dissolve it. Yet this sovereignty is inherently ambivalent: the same measures that protect against foreign manipulation enable domestic repression. The choice for peripheral states is not between freedom and control but between subordination to imperial platforms or subordination to domestic power—with the emancipatory possibility of neither fully realized.The struggle for digital sovereignty is the defining battle of the multipolar interregnum. There is no stable "nomos of the earth" for cyberspace—no accepted legal framework, no legitimate authority, no shared rules of engagement. Instead, there is a violent, contested scramble to impose order through technological dominance. This is digital anarchy: not the absence of rules but the presence of multiple, incompatible rule-systems enforced by power rather than legitimacy. The "liberal international order" presumed a single, open internet; its decomposition generates competing digital blocs that preclude the reconstitution of any stable hegemony.

I. The Protocol Stack as Neo-Sphere of Influence

The competition for digital dominance operates across layers of the protocol stack—physical, network, transport, and application—each constituting a distinct terrain of geopolitical contest. This is a neo-Mackinderian struggle where hegemony means controlling the pipes, not merely the content that flows through them. The prize is not territory in the classical sense but structural position: the capacity to extract tribute, surveil populations, and deny adversaries the means of modern existence.

The Physical Layer: Cables, Data Centers, and Chokepoints

Undersea cables carry 99% of international data traffic. Their geography is not neutral: the same routes that enabled British imperial telegraph networks now concentrate global connectivity in corridors vulnerable to interception and sabotage. The Five Eyes intelligence alliance maintains systematic access to this infrastructure through corporate partnerships and direct tapping operations—most notoriously the Tempora program exposed by Snowden, which harvests data from transatlantic cables at scale.

The strategic significance of physical infrastructure has intensified with the recognition that data localization is a fiction without local processing capacity. The vast data centers powering cloud computing concentrate in territories with cheap energy and lax regulation—Virginia, Oregon, Ireland, Singapore—creating dependencies that states struggle to overcome. China's East Data West Computing project and the EU's Gaia-X initiative represent attempts to reclaim this physical layer, but both remain substantially dependent on foreign semiconductor and software supply chains.

The Network Layer: 5G/6G and Satellite Constellations

The transition to 5G and prospective 6G networks has become the central battleground of technological competition. The Huawei exclusion campaign led by the United States—pressuring allies to ban Chinese equipment through sanctions threats and intelligence sharing—demonstrates that network infrastructure is now treated as military-critical. The official rationale (security vulnerabilities, backdoors) masks a deeper concern: whoever controls 5G infrastructure controls the data flows of the next generation, with implications for surveillance, economic competitiveness, and wartime operations.

The emergence of low-earth orbit satellite constellations—Starlink, China's Guowang, Amazon's Kuiper—extends this competition to space. Starlink's deployment in Ukraine (2022-) and its threatened use in Taiwan (2023-) and most recently in Iran (2026) demonstrate how satellite internet has become instrument of both military communications and geopolitical leverage. The ability to deny or provide connectivity from orbit represents a new form of spatial power that bypasses terrestrial infrastructure entirely.

The Transport and Application Layers: Clouds, Payments, and Platforms

Cloud infrastructure—AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, Alibaba Cloud—constitutes the computational substrate of modern state and economy. The dominance of US-based providers (approximately 65% of global market share) creates structural dependencies that translate directly into political leverage. The threat of cloud sanctions—denial of service to state entities, frozen data assets, terminated contracts—has become a standard instrument of coercion, deployed against Russia (2022) and threatened against others.

The financial messaging layer reveals the integration of digital and monetary sovereignty. SWIFT, nominally a Belgian cooperative, functions as instrument of US extraterritorial jurisdiction through Treasury Department enforcement. The exclusion of Iranian (2012, 2018) and Russian (2022) banks demonstrates that digital disconnection from the global financial system is now a primary form of economic warfare. Chinese (CIPS) and Russian (SPFS) alternatives remain marginal, not for technical inadequacy but because of network effects and trust deficits that no alternative system can quickly overcome.

Protocol Extraction: Beyond Hudson's Tribute

Michael Hudson's analysis of financial extraction through debt and monetary dominance must be extended to protocol extraction. States dependent on foreign-controlled infrastructure pay not merely in data surveillance but in structural vulnerability—the permanent possibility of disconnection, denial, or sabotage. The "tribute" levied by digital hegemons includes:

- Data tribute: Exfiltration of national information resources for commercial and intelligence exploitation

- Monetary tribute: Fees, compliance costs, and regulatory arbitrage profits extracted through control of payment systems

- Strategic tribute: Political concessions extracted through threat of infrastructure denial

The extraction is systemic, not transactional. It does not require specific policy decisions by the hegemon but operates through the architecture of dependence itself. This is the digital correlate of Hudson's "super imperialism": a form of dominance that persists regardless of which party holds office in the imperial center, embedded in the technical and institutional infrastructure of global connectivity.

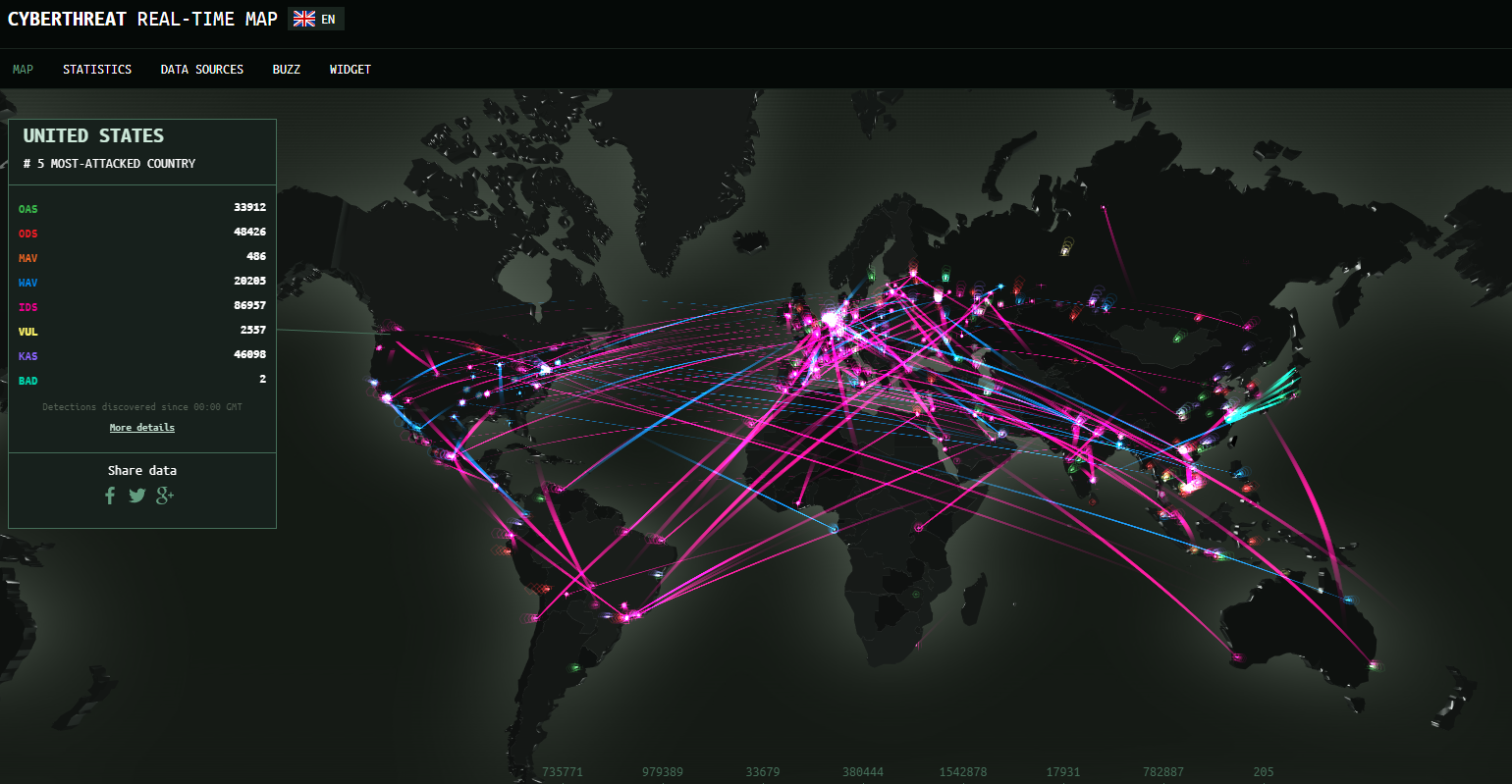

II. The Weaponization of Cognitive Infrastructure

Modern warfare has dissolved the distinction between peace and war into a continuum of cognitive operations. The platform infrastructure that fragments attention and disables deliberation domestically becomes, in international conflict, a delivery system for deception, demoralization, and social fragmentation. The same design features that generate cognitive twitchiness in ordinary use—variable rewards, emotional arousal, epistemic fragmentation—are intentionally exploited to render target populations incapable of coherent political response.

Integrated Hybrid Warfare: The 2022 Viasat Precedent

The Russian cyber-attack on Viasat satellite modems (February 24, 2022)—executed simultaneously with the ground invasion—established the integration of digital and kinetic operations as standard doctrine. The attack disabled Ukrainian military communications and thousands of civilian wind turbines across Europe, demonstrating that cyber effects cascade across military-civilian boundaries. The "dual-use" nature of digital infrastructure—civilian and military applications sharing common platforms—means that attacks on "military" targets inevitably generate civilian harm, and vice versa.

This integration extends to platform-enabled targeting. The use of commercial satellite imagery (Maxar, Planet Labs) for artillery correction, of social media geolocation for strike validation, and of facial recognition for casualty identification demonstrates that the civilian platform ecosystem has become military infrastructure. The distinction between "combatant" and "non-combatant," already eroded by twentieth-century counterinsurgency, dissolves entirely in the platform battlespace.

The Gaza Laboratory: Exportable Repression

The Israeli assault on Gaza (2023-) has served as the most intensive testing ground for AI-enabled population control and automated targeting. The "Lavender" and "Where's Daddy?" systems—AI-generated targeting lists with minimal human oversight—represent a qualitative escalation in the automation of lethal decision-making. The scale of target generation (tens of thousands), the compression of decision time (seconds of human review), and the acceptance of mass civilian casualties as "acceptable error rates" establish precedents with global implications.

More significant than the specific technologies is the political economy of their diffusion. Israeli firms—Elbit, NSO Group, Cellebrite, and numerous others—market these systems as "battle-proven" in Gaza and the West Bank. The commodification of experimental violence against captive populations creates a feedback loop: testing generates data, data refines algorithms, algorithms attract export customers, revenue funds further R&D. The "Gaza laboratory" is not metaphor but industrial process.

The export markets extend well beyond traditional military buyers. Automated border control systems (based on Gaza-tested surveillance), predictive policing algorithms (adapted from occupation pattern recognition), and cyber-intelligence platforms (refined through Palestinian device compromise) find customers among authoritarian regimes worldwide. The European and American acquiescence to Israeli operations—military aid, diplomatic protection, technology partnerships—enables this diffusion even where specific applications would face legal prohibition.

The normalization effect is equally significant. Technologies tested in exceptional conditions (siege, occupation, counterterrorism) become standard equipment for domestic policing in metropolitan centers. The same facial recognition that identifies "militants" in Gaza identifies protesters in London. The same predictive algorithms that anticipate Palestinian demonstrations anticipate climate activism in German cities. The imperial periphery serves as testing ground for metropolitan control.

III. The Fencing of Regime Change: Digital Sanctions as Siege Warfare

The most consequential development in digital geopolitics is the emergence of systematic digital exclusion as instrument of regime change. Where twentieth-century intervention relied on covert action, economic sanctions, or military invasion, the twenty-first century has pioneered siege without walls—the use of digital infrastructure denial to cripple state capacity and precipitate internal collapse.

Financial-Tech Sanctions: The SWIFT Weapon

The exclusion of Iranian banks from SWIFT (2012, reimposed 2018) and of Russian banks (2022) demonstrates that disconnection from the global financial messaging system is now equivalent to economic blockade. The effects extend beyond the immediate target: third-country banks reduce transactions with sanctioned entities to avoid secondary sanctions; supply chains fragment; import-dependent populations suffer. The "precision" of financial sanctions is a fiction; their operation is systemic and collective.

The integration of financial and technological sanctions creates comprehensive digital quarantine. The 2022 measures against Russia included:

- SWIFT exclusion for selected banks

- Cloud service termination (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud)

- Software license revocation (Microsoft, Oracle, SAP)

- Semiconductor export controls (choking military and civilian industry)

- App store blockades (denying mobile functionality)

- Domain and certificate revocation (disrupting secure communications)

The cumulative effect is not merely economic pressure but de-modernization: the systematic stripping of capabilities that define contemporary statehood. The strategy assumes that affected populations will attribute suffering to their own government and demand policy change—a coercive mechanism operating through civilian harm that international law has failed to regulate.

Platform De-Platforming: Political Excommunication

The suspension of state media, government officials, and cultural figures from global platforms—most comprehensively applied to Russia (2022) but increasingly standard—represents a novel form of digital banishment. The "public sphere" that platforms constitute is not merely commercial service but infrastructure of contemporary politics; exclusion from it severs a society's capacity for external communication and self-representation.

The criteria for exclusion are opaque, discretionary, and politically contingent. The same platforms that enforce "community standards" against adversary states maintain profitable operations in allied authoritarian regimes. The "rules-based order" of platform governance is rules-based in appearance, power-based in operation.

For peripheral states, the lesson is clear: dependence on foreign-controlled platforms constitutes permanent vulnerability. The Chinese, Russian, and (to lesser extent) European alternatives represent not merely commercial competition but survival strategies against the possibility of sudden digital excommunication.

Infrastructure Sabotage: From Stuxnet to Normalization

The Stuxnet attack on Iranian nuclear facilities (2009-2010) established the precedent of preventive cyber warfare—the use of digital means to destroy physical infrastructure before operational use. The operation's exposure demonstrated both the feasibility and the risks of such attacks: the malware escaped into global circulation, infected unintended targets, and revealed capabilities that adversaries subsequently studied.

Despite this, the normalization of infrastructure sabotage has proceeded. The 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack (attributed to criminal actors but with state sanctuary), the 2022 Viasat attack, and numerous unacknowledged operations against Iranian, Syrian, and North Korean infrastructure establish that critical systems are permanently vulnerable. The "attribution problem"—difficulty of definitively identifying attackers—enables plausible deniability that erodes the stabilizing mechanisms of deterrence.

The strategic implications are profound. Mutual assured destruction, which prevented nuclear war through recognition of shared vulnerability, has no equivalent in cyberspace. The attacker typically retains escalation dominance; the defender cannot reliably retaliate; the threshold for "war" remains undefined. The result is permanent low-intensity conflict—the "gray zone" that favors the technologically superior party.

IV. The Sovereignty Dilemma: Emancipation and Repression

The "sovereign internet" projects of China, Russia, Iran, and others are routinely condemned in Western discourse as authoritarian aberrations—rejections of the "free and open internet" that supposedly represents global consensus. This framing obscures the structural necessity of such projects: for states facing the digital siege measures described above, control over national information infrastructure is as essential as control over national currency or military force.

The Chinese Model: Comprehensive Control as Development Strategy

China's internet governance—the Great Firewall, data localization requirements, platform regulation—represents the most developed alternative to US platform dominance. The system sacrifices individual liberty for collective strategic autonomy: protection against foreign manipulation, capacity for industrial policy, and maintenance of social stability.

The model is exportable. Chinese technology and regulatory frameworks find adoption across Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America—not merely through Belt and Road financing but through demonstration effect. States observing the consequences of digital dependence on the US (sanctions vulnerability, political interference, platform extraction) increasingly conclude that Chinese-style control is the lesser evil.

The contradiction is internal: the same infrastructure that protects against foreign manipulation enables domestic surveillance and suppression.

The Russian Model: Sovereignty as Reactive Defense

Russia's Runet project—accelerated after 2012, tested in 2019 "sovereign internet" drills, and fully activated after 2022—represents defensive adaptation under pressure rather than comprehensive alternative construction. The measures include:

- Technical: National DNS, traffic filtering, deep packet inspection

- Legal: Data localization, "foreign agent" designation for platforms, criminalization of "fake news"

- Economic: Development of domestic alternatives (Yandex, VK, Mir payment system)

- Coercive: Platform blocking, content removal demands, physical intimidation of tech workers

The Russian case demonstrates that sovereignty construction under fire is partial and contradictory. Despite extensive preparation, the 2022 sanctions exposed continued dependence on foreign infrastructure: cloud services, semiconductors, software licenses. The "sovereign internet" protects against some forms of external manipulation while leaving others unaddressed; it enables domestic control while degrading economic competitiveness.

The European Model: Regulatory Autonomy Without Independence

The European Union's approach—GDPR, Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act, Gaia-X—attempts to achieve public interest protection without sovereign independence. The strategy relies on regulatory extraterritoriality: imposing European standards on global platforms through market access threats, rather than constructing autonomous alternatives.

The limitations are structural. European cloud infrastructure (Gaia-X) remains marginal; European semiconductor production (European Chips Act) cannot eliminate dependence on Asian manufacturing; European platforms cannot overcome network effects that entrench US-Chinese dominance. The regulatory approach addresses symptoms (content moderation, data protection) while preserving underlying dependence (infrastructure, software, standards).

The European case illustrates the impossibility of middle positions in the digital sovereignty dilemma. Neither fully integrated into US infrastructure (like the UK) nor capable of autonomous construction (like China), the EU occupies an unstable position that regulatory ambition cannot stabilize.

The Peripheral Gamble: Strategic Maneuvering in Digital Anarchy

For states outside the core blocs, the digital sovereignty dilemma takes specific forms. India's data localization, digital payment infrastructure (UPI), and platform regulation demonstrate capacity for selective autonomy—leveraging market size to extract concessions, developing domestic alternatives in specific domains, maintaining strategic relationships with multiple suppliers. Brazil's LGPD and recent platform accountability measures show similar ambition, constrained by weaker enforcement capacity and the structural subordination of its financial sector to Wall Street clearinghouses.

Latin America, however, presents a distinctive structural opportunity obscured by current fragmentation. While individual national efforts—Chile's data protection frameworks, Colombia's cloud infrastructure initiatives, Mexico's fintech localization—remain vulnerable to the "multi-alignment" trap, the region collectively possesses the market scale, cultural cohesion, and resource base to establish genuine digital sovereignty. The critical missing element is the transformation of disparate national policies into a unified continental strategy for material and cultural development in the twenty-first century.

The "multi-alignment" strategy—participating in Chinese digital infrastructure (Huawei, Belt and Road Digital) while maintaining US platform dependence (Google, Meta, AWS)—generates tactical flexibility but strategic vulnerability. Latin American states currently negotiate from weakness: individual republics facing transnational platform monopolies secure only marginal concessions regarding data residency or revenue sharing, while their elites remain integrated with the extractive circuits of Big Tech. The assumption that competition between US and Chinese digital empires creates space for autonomous maneuver assumes that neither hegemon will demand exclusive alignment.

The alternative lies in treating digital sovereignty not as regulatory afterthought but as the central pillar of regional development in the twenty-first century. Latin America could establish autonomous capacity through coordinated action across five strategic domains:

- Regional Collaboration – Beyond bilateral trade agreements, the region requires a digital integration pact establishing shared data governance standards, cross-border privacy protocols, and collective bargaining positions vis-à-vis foreign platforms. The EU's GDPR demonstrated that regulatory scale generates compliance from global corporations; a unified Latin American digital market of 650 million consumers could demand—and enforce—genuine data residency, algorithmic transparency, and revenue sharing that individual states cannot secure alone.

- Locally-Designed AI – The development of regional language models such as Latam-GPT trained on Spanish, Portuguese, and indigenous language, represents both cultural sovereignty and economic necessity. Current generative AI systems encode Anglo-American cultural assumptions and extract value through API fees while depriving local linguistic communities of data dividends. Sovereign AI development—trained on regional data repositories governed by local institutions—would prevent the cognitive colonialism embedded in imported models and retain value chains domestically.

- Data Sovereignty & Infrastructure – The region must transition from cloud consumption to infrastructure ownership. This requires public investment in sovereign data centers, submarine cable landing points independent of US filtering, and regional cloud alternatives to AWS and Azure. Such infrastructure would not merely store data locally but process it through systems governed by regional legal frameworks, preventing the jurisdictional arbitrage that currently allows platform extraction.

- Strategic Planning for Tech – Technology policy must be elevated to the level of macroeconomic planning, treated with the same urgency as central banking or trade balances. This requires national and regional development banks financing local software industries, procurement policies favoring free and open-source solutions over proprietary foreign licenses, and industrial policy targeting the entire stack—from undersea cables to application layers—rather than mere assembly or consumption.

Policy & Regulatory Frameworks – Unifying existing fragmented legislation (Brazil's LGPD, Mexico's Fintech Law, Chile's Data Protection Act) into a harmonized regional framework that prioritizes interoperability with Global South partners over compliance with Silicon Valley standards. Crucially, this framework must address the specific modality of peripheral extraction: not merely privacy protection but value retention, ensuring that data generated within the region produces economic returns and technological capabilities locally rather than enriching distant shareholders.

V. Digital Anarchy and the Interregnum

Wolfgang Streeck's analysis of institutional decomposition—the hollowing of democratic capacity, the erosion of collective bargaining, the collapse of party systems—finds its international correlate in the disintegration of digital order. The "liberal international order" presumed a single, open internet governed by multi-stakeholder processes and market mechanisms; its decomposition generates competing digital blocs that preclude the reconstitution of any stable hegemony.

This is digital anarchy: not the absence of rules but the presence of multiple, incompatible rule-systems enforced by power rather than legitimacy. The condition is characterized by:

- Strategic uncertainty: No stable expectations about which infrastructure will function, which data will be secure, which connections will be permitted

- Escalatory instability: No agreed thresholds for "war" in cyberspace, no established mechanisms of deterrence or crisis management

- Regulatory arbitrage: Continuous relocation of operations to evade national controls, undermining both sovereignty and public interest regulation

- Technological acceleration: Competitive pressure for AI, quantum computing, and autonomous systems that outpaces institutional capacity for governance

The anarchy is productive for the dominant powers in specific ways. US platform dominance extracts global tribute; Chinese infrastructure exports create dependencies; both benefit from the fragmentation that prevents third-country collective action. Yet it is also destructive: the same instability that weakens adversaries undermines the predictability necessary for global commerce and, ultimately, for imperial management itself.

Conclusion: Toward a Political Economy of Digital Conflict

The analysis suggests that digital sovereignty, however contradictory, is the necessary terrain of struggle. There is no "outside" to platform militarism, no space of authentic communication uncontaminated by infrastructure politics. The only possible emancipatory politics must be constructed through and against the infrastructure of control, not in imagined spaces beyond it.

This requires strategic clarity

- Recognition that digital sovereignty is ambivalent—protective and repressive, emancipatory and authoritarian—whose specific valence depends on political struggle rather than technical design

- Rejection of technocratic solutions—international governance frameworks, "rules-based" cyberspace, multi-stakeholder processes—that presume a stability the interregnum denies

- Insistence on class and peripheral agency—the possibility that subordinate states and populations can leverage competitive dynamics among hegemons, develop autonomous capacities, and resist both imperial extraction and domestic repression

- the refusal of easy optimism about technological progress or international cooperation—while preserving the possibility of politics: the stubborn insistence that collective agency remains decisive even in conditions of radical unfreedom

The colonization of consciousness analyzed in the preceding article and the weaponization of infrastructure examined here are moments of a single process: the transformation of digital technology from potential instrument of human emancipation into apparatus of domination. The struggle against this transformation—for digital sovereignty that serves popular rather than imperial power—is thus inseparable from the broader struggle against financialized extraction, ecological destruction, and militarized competition that defines our times.

The digital battlefield is not metaphor. It is the actual terrain on which the possibility of any future politics will be determined. Understanding its geography—its chokepoints, its vulnerabilities, its potential for reversal—is prerequisite for any strategy that would navigate the coming decades without catastrophic submission.

References and Further Reading

Core Political Economy Framework

- Hudson, Michael (1972/2003). Super Imperialism: The Economic Strategy of American Empire. New York University Press.

- Hudson, Michael (2015). Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy. ISLET-Verlag.

- Streeck, Wolfgang (2016). How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System. Verso Books.

- Arrighi, Giovanni (1994). The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. Verso Books.

Cyber Warfare and Digital Conflict

- Rid, Thomas (2013). Cyber War Will Not Take Place. Oxford University Press.

- Valeriano, Brandon & Jensen, Benjamin (2019). The Dynamics of Cyber Conflict. Oxford University Press.

- Segal, Adam (2016). The Hacked World Order: How Nations Fight, Trade, and Maneuver in Cyberspace. PublicAffairs.

- Kello, Lucas (2017). The Virtual Weapon and International Order. Yale University Press.

Platform Militarization and Surveillance

- Zuboff, Shoshana (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs.

- Greenwald, Glenn (2014). No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State. Metropolitan Books.

- Lewis, John & Schwarz, Ari (2023). "The Gaza Laboratory: AI and Automated Warfare." +972 Magazine investigations (April 2024).

- Hever, Shir (2018). The Privatization of Israeli Security. Pluto Press.

- Flyverbom, Mikkel (2019). The Digital Prism: Transparency and Managed Visibilities in a Datafied World. Cambridge University Press.

- Maurer, Tim (2022). Cyber Mercenaries: The State, Hackers, and Power. Cambridge University Press.

Geopolitics of Infrastructure

- Starosielski, Nicole (2015). The Undersea Network. Duke University Press.

- Müller, Daniel (2021). "The Political Economy of Submarine Cables." Review of International Political Economy.

- Farrell, Henry & Newman, Abraham (2019). "Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion." International Security.

- Shen, Yi (2020). "Cyber Sovereignty and the Governance of Global Cyberspace." Chinese Political Science Review.

Financial Warfare and Sanctions

- Mulder, Nicholas (2022). The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War. Yale University Press.

- Farrell, Peter & Newman, Abraham (2023). Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy. Henry Holt.

- Meister, Aaron (2019). "SWIFT, Sanctions, and the Future of Financial Messaging." Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Digital Sovereignty and Internet Governance

- Deibert, Ronald (2020). Reset: Reclaiming the Internet for Civil Society. House of Anansi Press.

- Mueller, Milton (2017). Will the Internet Fragment? Sovereignty, Globalization and Cyberspace. Polity Press.

- Creemers, Rogier (2022). "Cyber Sovereignty: The Global Spread of a Chinese Concept." Made in China Journal.

- Elsheikh, Marwa (2023). "The Splinternet: How Geopolitics and Commerce are Fragmenting the World Wide Web." Chatham House.

Want to stay informed about global economic

trends?

Subscribe to our newsletter for weekly analysis and insights

on international politics and economics.