The Demographic Transition as Political Crisis (2026)

Aging, Youth Bulges, and the Structural Impossibility of Managed Migration

By Michel Chen

The demographic transformation of the early twenty-first century has been assimilated into policy discourse with characteristic delay. Population aging in wealthy societies and youth concentration in poor ones are recognized as structural features requiring response, but the responses proposed—pension reform, skilled immigration, automation, development promotion—assume continuities that the transformation itself dissolves. The demographic transition is not merely quantitative change in age structure but qualitative transformation of political possibility: the erosion of social contracts based on intergenerational transfer, the destabilization of labor markets and state finances, the generation of migration pressures that border regimes cannot manage, and the creation of youth populations whose exclusion from productive participation threatens systemic legitimacy.

The analysis that follows examines three interconnected dimensions: the aging of wealthy societies and the impossibility of pension and care systems as currently structured; the youth bulges of the periphery and their exclusion from developmental promise; and the migration that connects these dynamics and that state violence can brutalize but never resolve. The conclusion assesses whether demographic transformation can be navigated through institutional adaptation within existing structures, or whether it generates contradictions that require fundamental transformation of property relations and global distribution.

The Graying Core: Pension Systems and the Erosion of Intergenerational Contract

The wealthy societies of the OECD face unprecedented aging. Median ages exceed forty in most; in Japan, Italy, Germany, they approach fifty. Fertility rates have remained below replacement for decades; population decline has begun in Japan and several European states; immigration has partially offset demographic contraction but cannot reverse it without politically impossible volumes. The result is a structural transformation: the ratio of workers to retirees, which sustained postwar pension systems at roughly five-to-one, has fallen below three-to-one and approaches two-to-one in the most aged societies.

The pension systems established in the postwar decades assumed demographic stability: contributions from employed workers would fund benefits for retired ones, with modest reserves invested in government securities. The pay-as-you-go structure was sustainable while age pyramids were favorable and employment rates high. The demographic transition renders it unsustainable: the same benefits require increased contributions from diminished workforces, or reduced benefits for expanded retiree populations, or some combination that generates political opposition from both workers and retirees.

The "reforms" implemented through recent decades—retirement age increases, contribution hikes, benefit reductions, privatization of partial accounts—have partially addressed fiscal imbalance while generating distributional conflict and political instability. The French pension protests of 2023, the German coalition crises over retirement policy, the Japanese consumption tax increases to fund elder care—these indicate the difficulty of adjustment within democratic frameworks. The alternative of significant immigration to replenish workforces encounters cultural and political resistance that has strengthened far-right formations across Europe.

The care economy presents comparable pressures. Longer life expectancy extends the period of dependency and care need; smaller families reduce informal care provision; women's labor force participation limits traditional family-based care; state provision requires fiscal resources that aging workforces cannot generate. The result is "care crisis" that manifests in inadequate provision, exhausted informal caregivers, and political conflict over funding and organization. The technological fixes proposed—robot care, remote monitoring, AI assistance—remain insufficient and ideologically motivated substitutes for human labor that market mechanisms cannot allocate.

The intergenerational conflict that demographic transformation generates is not merely fiscal but cultural and political. The asset positions of older cohorts—housing wealth, pension claims, financial investments—depend upon continued asset appreciation that younger cohorts cannot achieve through equivalent effort. The "generation rent" phenomenon in housing markets, the student debt burdens that delay wealth accumulation, the precarious employment that prevents stable family formation—these create structural antagonism between age cohorts that political rhetoric of "solidarity" cannot resolve. This is not just conflict over slices of a shrinking pie, but conflict over the recipe for the pie itself—a struggle between a gerontocratic politics of asset preservation and a youth-facing politics of systemic overhaul. The electoral dominance of older voters in aging societies ensures that policy responds to their interests, deepening the exclusion of younger cohorts.

The Youth Periphery: Exclusion and Its Discontents

The demographic profile of the global periphery inverts that of the core. Median ages below twenty-five in much of sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia; fertility rates that remain at or above replacement despite declining trends; youth populations that expand absolutely even as growth rates moderate. The "youth bulge"—proportion of population aged fifteen to twenty-nine exceeding historical averages—creates structural conditions that developmental promise cannot satisfy.

The postwar developmental paradigm assumed that industrialization would absorb rural surplus labor into urban manufacturing, generating the demographic transition through fertility decline as incomes rose and child survival improved. This sequence occurred in East Asia and parts of Latin America, but has stalled or failed in much of Africa and the Middle East. Deindustrialization in the core, automation of manufacturing, and competition from established exporters close the path that earlier developers followed. The "middle-income trap" that development economics identifies is experienced by many states as permanent exclusion from the developmental promise.

The educational expansion that accompanied developmental aspiration has created credential inflation without employment absorption. University graduates drive taxis, sell mobile phones, or remain unemployed in Cairo, Lagos, Jakarta, Dhaka. The informal economy absorbs labor without providing stable income, social protection, or career progression. The "waithood" that youth experience—prolonged dependence, delayed marriage, frustrated aspiration—generates psychological and political effects that stability-oriented analysis cannot capture. The "waithood" generation is not waiting passively; it is the human feedstock for the climate, migration, and potential conflict crises that define our interregnum.

The political responses to this exclusion vary: religious mobilization, nationalist assertion, migration, criminal participation, or resigned adaptation. The Arab uprisings of 2011, the "youth bulge" analysis that informed their interpretation, and their subsequent repression or co-optation demonstrated both the political potential and the organizational difficulties of youth mobilization. The authoritarian consolidation that followed—military restoration, monarchical reinforcement, civil war fragmentation—indicated the ruling class capacity for violent response rather than developmental address.

The environmental dimension compounds demographic pressure. Climate change reduces agricultural productivity in tropical regions, accelerates urbanization, and generates migration pressures that existing institutions cannot manage. The "climate-migration nexus" that policy discourse identifies is experienced by youth populations as lived contradiction: their territories become uninhabitable through processes they did not cause, while the wealthy societies responsible for those processes erect barriers to their movement. The temporal mismatch—decades of climate impact, immediate migration pressure—generates political effects that reactive policy cannot address.

Migration: The Structural Necessity and Political Impossibility

The demographic divergence between aging core and youthful periphery generates migration pressure that is structurally necessary and politically unmanageable. The labor needs of aging societies—care workers, construction labor, agricultural workers, service employees—could be substantially met through immigration from labor-surplus regions. The income differentials that persist despite globalization—wage ratios of ten-to-one or greater between wealthy and poor societies—provide economic motivation for movement that enforcement cannot eliminate. The demographic transition thus generates migration that is simultaneously economically rational and politically explosive.

The policy responses have converged on "managed migration" that manages neither the economic needs of receiving societies nor the human needs of migrants. Visa regimes favor skilled migration that deprives sending societies of needed professionals; temporary worker programs create precarious populations without rights or permanence; asylum systems are overwhelmed by applications that procedural obstruction cannot deter; irregular migration is criminalized and subjected to increasingly violent border enforcement. The result is neither closed borders nor open movement, but a proliferating infrastructure of detention, deportation, and death that generates profit for private contractors and legitimacy for nationalist politics.

The European experience demonstrates the political dynamics. The 2015 "crisis"—refugee flows from Syria and adjacent conflicts—generated institutional responses (the EU-Turkey deal, border externalization, Frontex expansion) that did not resolve underlying pressures but displaced them to more dangerous routes and more vulnerable populations. The subsequent "migration management" has reduced arrivals while maintaining the infrastructure of enforcement; the far-right formations that gained from 2015 have consolidated rather than receded; the "solidarity" mechanisms for intra-EU burden-sharing have failed. The demographic divergence that drives migration has intensified while political capacity for response has diminished.

The American experience parallels with distinctive features. The demographic aging of the native-born population, the labor market needs of service and agricultural sectors, and the historical presence of Latin American diaspora communities generate migration pressures that enforcement cannot eliminate. The political response oscillates between amnesty proposals that Republican opposition blocks and enforcement escalation that Democratic constituencies oppose. The "border crisis" that media framing identifies is permanent structural feature rather than temporary emergency; the political system responds through spectacle rather than policy.

The technological and infrastructural dimensions of border enforcement merit specific attention. The "smart border" infrastructure—surveillance systems, biometric databases, automated detection, drone patrol—replicates the military-technological complex analyzed in the Gaza discussion, with Israeli and other "battle-proven" systems finding application in migration control. The border is not merely territorial but biometric and digital: the body itself becomes site of enforcement through identification, tracking, and exclusion. The infrastructure investment that this requires—walls, detention facilities, surveillance systems—generates constituencies with interest in perpetual "crisis."

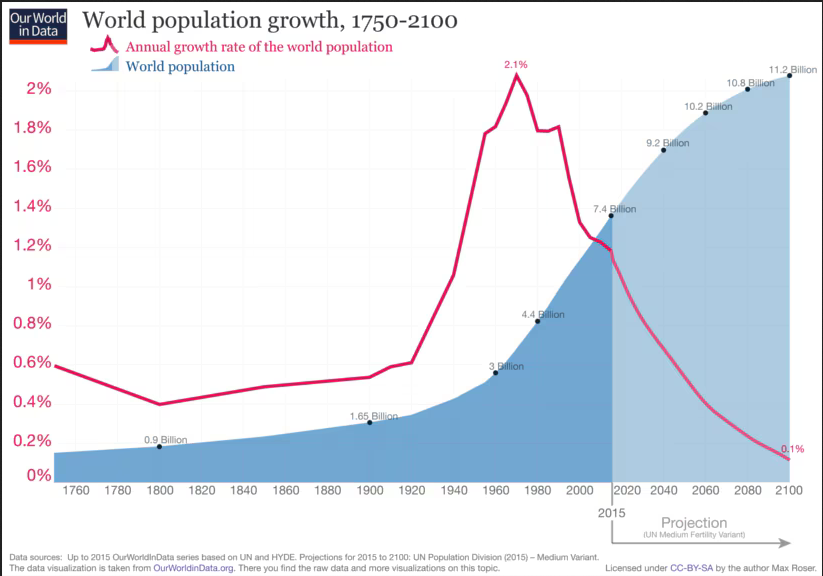

This chart comes from Our World in Data by economist Max Roser, and it shows how global demographics will shift over the next 80 years.

The Political Economy of Demographic Management

The demographic transition generates profitable opportunities that shape policy response. The pension fund industry—asset management for retirement savings—has grown to control trillions in investable capital, with political influence commensurate to its size. The "silver economy"—products and services for aged populations—expands as demographic weight shifts. The care industry—private provision of elder and child care—converts familial obligation into market transaction. The security industry—border enforcement, detention, surveillance—profits from migration control. The demographic transition is thus not merely problem for policy but opportunity for accumulation.

The financialization of pension provision illustrates the structural dynamics. The shift from pay-as-you-go to funded systems, partial or complete, transfers risk from state to individual and generates fee income for financial intermediaries. The "defined contribution" structures that replace "defined benefit" promises subject retirement security to market fluctuation that individuals cannot manage. The asset appreciation that funded systems require depends upon economic growth rates that aging workforces cannot sustain. The result is systemic risk that periodic crises reveal but institutional inertia prevents addressing.

The care economy similarly exhibits financialization pressures. Private equity acquisition of care facilities, cost-cutting that reduces quality, labor exploitation that generates high turnover, and regulatory capture that prevents accountability—these patterns replicate across national contexts. The "crisis" of care is not merely quantitative insufficiently but qualitative degradation through profit extraction. The technological fixes proposed—automation, remote monitoring, AI assistance—serve to reduce labor costs rather than improve care quality, and their implementation proceeds through public subsidy for private profit.

The migration control industry—private detention facilities, surveillance technology contractors, deportation services—has achieved substantial scale and political influence. The "crimmigration" convergence of criminal and immigration law generates detainable populations that justify facility construction. The technological upgrading of border enforcement—biometric identification, predictive analytics, automated response—requires continuous investment that periodic "crises" legitimate. The industry has structural interest in migration pressure continuation rather than resolution.

Beyond these established sectors, the combined weight of unfunded pension liabilities, future care needs, and climate-driven migration pressures creates a "demographic overhang"—a massive, deferred claim on future economic output that the current growth and fiscal model cannot possibly meet. This overhang functions as a socio-economic time bomb, guaranteeing that the political conflicts over distribution will intensify rather than subside.

The Critical Anomaly: China's Precarious Experiment

The Chinese model represents a catastrophic test case that shatters the simple Core/Periphery binary. Through its One-Child Policy, China achieved the demographic transition of an advanced economy—rapid aging, low fertility—while retaining, until recently, the per capita income and social infrastructure of a developing one. It now faces core-like aging (a shrinking workforce, a soaring dependency ratio) with periphery-like needs for employment and social stability, all while financing vast military and geopolitical ambitions. Its attempt to navigate this via automation, internal migration from rural to urban areas, and strategic economic anxiety may determine whether any political system can manage such a severe demographic reversal. China’s demographic crisis is not a future event; it is the present condition that will dictate the limits of its rise and the stability of its system.

Ideological Responses: Nationalism, Natalism, and Techno-Fix

The demographic transformation generates ideological responses that legitimate non-response or misdirect address. Nationalist formations across the core mobilize against immigration as threat to cultural identity and social cohesion, offering demographic restoration through fertility promotion that policy cannot achieve. The "great replacement" rhetoric that circulates in far-right discourse racializes demographic transition and justifies exclusionary violence. The electoral success of such formations—Le Pen, Orbán, Meloni, Trump and successors—indicates the political potency of demographic anxiety.

The natalist policies implemented by some governments—family benefits, parental leave, childcare provision—have marginal effects on fertility rates that remain below replacement. The Scandinavian model that social democrats promote achieves higher fertility than liberal market societies, but not replacement levels; the investment required is substantial and politically contested; the effects are long-term while political horizons are short. The "pro-natalism" that some conservative governments promote combines with anti-immigration positioning to generate incoherent policy that addresses neither aging nor labor needs.

The technological fixes proposed—automation, AI, robotics—promise to substitute capital for labor in care, production, and services. The analysis in previous articles has assessed these promises skeptically: the technologies remain insufficient, their deployment generates contradictions, their political function is to defer address of structural problems. The demographic application of techno-fix—"care robots," "AI companions," automated service delivery—reproduces these patterns: promise without delivery, substitution without sufficiency, profit without provision.

The "development" framing for periphery youth—education, entrepreneurship, digital connection—similarly promises resolution without structural transformation. The "demographic dividend" that development economics identifies requires employment absorption that global economy cannot provide; the "youth employment" programs that international organizations promote are insufficient in scale and inappropriate in structure; the "start-up" ideology that celebrates entrepreneurial individualism obscures collective failure to generate livelihood. The framing functions to blame youth for their exclusion rather than transforming the structures that exclude them.

Conclusion: Demography as Destiny or Politics

The demographic transition presents itself as natural process requiring policy adaptation, but its political effects are structurally transformative. The aging of wealthy societies erodes the social contracts that maintained legitimacy through postwar decades; the youth concentration in poor societies generates pressures that developmental promise and repressive response cannot manage; the migration that connects these dynamics produces political crises that reactive policy exacerbates. The "management" that policy discourse proposes—pension reform, skilled immigration, automation investment, development promotion—addresses symptoms without transforming causes.

The alternative—genuine transformation of global distribution, public ownership of pension and care systems, open borders with full social rights, investment in youth employment and climate adaptation—requires political mobilization that existing structures prevent. Concrete proposals, such as a Global Care and Climate Corps funded by a financial transaction tax—offering young people in the periphery paid, dignified work in care and climate adaptation with pathways to mobility—could begin to link these crises practically. Yet such measures remain outside the bounds of mainstream discourse.

The nationalist formations that have gained from demographic anxiety offer exclusion and restoration rather than transformation; the social democratic formations that might propose alternative adaptation have accommodated to neoliberal constraint; the revolutionary formations that might demand fundamental transformation remain fragmented and suppressed.

The temporal dimension is decisive: demographic transformation proceeds through generational replacement that political mobilization cannot accelerate, while climate and ecological deadlines impose absolute constraints that demographic adaptation cannot extend. The "intergenerational justice" framing that some propose—sacrifice for future generations, climate action for descendants—collides with the electoral dominance of older cohorts and the immediate pressures that youth populations experience. The political system as constituted cannot reconcile these temporalities.

The demographic transition thus joins energy, AI, and military transformation as dimension of structural crisis that imperial decline intensifies rather than resolves. The American empire's capacity for global management—developmental, migratory, environmental—has eroded with its productive base and ideological appeal. The competitive dynamics with China and other rising powers distort cooperative response that demographic and ecological interdependence requires. The conclusion that previous articles reached extends: the interregnum between orders is characterized by multiple, overlapping crises that neither declining hegemon nor rising challengers can resolve within existing structures. The interregnum's defining question may be this: Will the unprecedented number of young people with no stake in the present system find a common language with the growing number of old people betrayed by it, before both are drowned by the rising tides it has unleashed?

References

Organized by Analytical Themes

Demographic Overhang and Intergenerational Conflict

Core Claim: Unfunded pension liabilities, future care needs, and climate migration pressures constitute a deferred claim on future output that current growth models cannot meet.

- Kotlikoff, Laurence J. and Burns, Scott — The Clash of Generations: Saving Ourselves, Our Kids, and Our Economy (2012). Documents generational accounting and the fiscal impossibility of current commitments.

- Goodhart, Charles and Pradhan, Manoj — The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival (2020). Analyzes the macroeconomic effects of aging and dependency ratio shifts.

- Hudson, Michael — Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy (2015). Examines the financialization of pensions and the extraction of rent through intergenerational transfers.

- Lee, Ronald and Mason, Andrew (eds.) — Population Aging and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective (2011). Authoritative empirical study of national transfer accounts and dependency burdens.

- Settersten, Richard A. and Angel, Jacqueline L. — Handbook of the Sociology of Aging (2011). Provides sociological framework for understanding intergenerational equity and conflict.

China's Demographic Anomaly

Core Claim: China faces core-like aging before achieving core-like wealth, creating unprecedented structural pressures that threaten its economic model.

- Yi, Fuxian — Big Country with an Empty Nest (2007, Chinese). Early and influential critique of the One-Child Policy and its demographic consequences.

- Wang, Feng, Cai, Yong, and Gu, Baochang — “Population, Policy, and Politics: How Will History Judge China’s One-Child Policy?” Population and Development Review (2013). Authoritative demographic analysis.

- Magnus, George — Red Flags: Why Xi’s China Is in Jeopardy (2018). Examines the intersection of demographic decline with economic and political challenges.

- Bricker, Darrell and Ibbitson, John — Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline (2019). Places China’s fertility collapse within a global context.

- World Bank Group — Live Long and Prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific (2016). Regional report detailing the speed and scale of aging, with special focus on China.

The Care Crisis and Social Reproduction

Core Claim: The care crisis is fundamentally a crisis of social reproduction historically resolved by women's unpaid labor, now commodified without resolution.

- Fraser, Nancy — “Contradictions of Capital and Care.” New Left Review 100 (2016). Theoretical framework linking social reproduction crises to financialized capitalism. Federici, Silvia — Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (2012). Foundational analysis of unwaged reproductive labor.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell — The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times (2012). Examines the marketization of care and emotional labor.

- Mies, Maria — Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour (1986). Classic work on the global gendered division of labor.

- International Labour Organization (ILO) — Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work (2018). Global data on the care economy and its undervaluation.

Youth Bulges, Exclusion, and Political Instability

Core Claim: Youth concentration in the periphery without developmental absorption generates systemic political pressures.

- Urdal, Henrik — “A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence.” International Studies Quarterly 50.3 (2006). Key empirical study linking demography to conflict risk.

- Singerman, Diane — “The Economic Imperatives of Marriage: Emerging Practices and Identities among Youth in the Middle East.” Middle East Youth Initiative Working Paper (2007). Groundbreaking work on “waithood.”

- Honwana, Alcinda — The Time of Youth: Work, Social Change, and Politics in Africa (2012). Ethnographic analysis of youth agency and exclusion in Africa.

- Cincotta, Richard P. — “Youth Bulge, Underemployment Raise Risks of Civil Conflict.” New Security Beat, Wilson Center (2017). Geopolitical analysis of demographic security risks.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) — World Youth Report: Youth and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2018). Official data on global youth employment and education gaps.

Migration and the Border-Industrial Complex

Core Claim: Demographic divergence generates migration that is structurally necessary and politically unmanageable, fueling a profitable enforcement infrastructure.

- De Haas, Hein, Castles, Stephen, and Miller, Mark J. — The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World (6th ed., 2020). Definitive textbook on global migration dynamics.

- Andersson, Ruben — Illegality, Inc.: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe (2014). Ethnography of the migration control industry.

- Miller, Todd — Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the US Border Around the World (2019). Investigates the globalization of border security and its political economy.

- Brown, Wendy — Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (2010). Theoretical analysis of border walls as symbols of eroding state power.

- Global Detention Project — Various reports on immigration detention worldwide. Provides data on the scale and privatization of detention.

Financialization of Life-Cycle Services (Pensions, Care, Housing)

Core Claim: Demographic transformation generates profitable opportunities that shape policy toward marketization and financial extraction.

- Blackburn, Robin — Banking on Death: Or, Investing in Life: The History and Future of Pensions (2002). Seminal work on pension fund capitalism.

- Christophers, Brett — Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? (2020). Analysis of assetization, including housing and pensions.

- Engelen, Ewald — “The Logic of Funding European Pension Restructuring and the Dangers of Financialisation.” Environment and Planning A 35.8 (2003). Examines the financialization of pension systems.

- Federal Reserve Board — Survey of Consumer Finances (2022). Data on intergenerational wealth inequality and housing asset concentration.

- Mackenzie, Donald — Material Markets: How Economic Agents are Constructed (2009). Sociology of the financial instruments built around demographic “risk.”

Nationalism, Nativism, and the Politics of Demographic Anxiety

Core Claim: Far-right formations mobilize demographic anxiety to legitimate exclusion and defer structural transformation.

- Mudde, Cas — The Far Right Today (2019). Overview of contemporary far-right ideology, including demographic and nativist themes.

- Kaufmann, Eric — Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities (2018). Controversial but influential analysis of ethnicity and demographic change in Western politics.

- Farris, Sara R. — In the Name of Women's Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism (2017). Examines how gender equality is instrumentalized for nationalist and anti-immigrant agendas.

- Mondon, Aurelien and Winter, Aaron — Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream (2020). Analyzes the mainstreaming of demographic replacement theory.

The Limits of the Technological Fix

Core Claim: Automation, AI, and robotics promises for demographic challenges reproduce patterns of techno-solutionism.

- Noble, David F. — Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation (1984). Classic historical critique of automation ideology. Winner, Langdon — The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology (1986). Philosophical critique of technological determinism.

- Sharkey, Amanda and Sharkey, Noel — “We Need to Talk About Deception in Social Robotics!” Ethics and Information Technology (2021). Critical analysis of “care robot” capabilities and ethics.

- OECD — The Future of Social Protection: What Works for Non-standard Workers? (2018). Reports demonstrating the limited impact of current automation on solving care and pension crises.

Climate, Migration, and Temporal Collapse

Core Claim: Climate change accelerates migration pressures that institutional responses cannot manage within relevant timelines.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Scientific basis for climate impacts on human systems and displacement.

- McLeman, Robert — Climate and Human Migration: Past Experiences, Future Challenges (2014). Historical and empirical study of the climate-migration nexus.

- Parenti, Christian — Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence (2011). Analyzes climate change as a conflict multiplier in vulnerable regions.

- Institute for Economics & Peace — Ecological Threat Register 2023. Global data linking ecological degradation, demographic stress, and instability.

Alternative Frameworks and Transitional Demands

Core Claim: Proposals for a Global Care and Climate Corps or similar systemic interventions remain outside mainstream possibility but indicate necessary directions.

- Mazzucato, Mariana — Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism (2021). Argues for mission-oriented public investment to address grand challenges.

- Kelton, Stephanie — The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy (2020). Provides a macroeconomic framework for large-scale public employment programs.

- Ghosh, Jayati — “A Global Green New Deal for Sustainable Development.” Journal of Globalization and Development 12.2 (2021). Proposes an internationally coordinated program for employment and transition.

- International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) — Frontlines of a Just Transition: A Global Toolkit for Trade Unions (2022). Labor movement proposals for linking climate action and job creation.

Intellectual Tradition and Overall Framing

The text’s overarching framework is most directly informed by:

- Wallerstein, Immanuel — World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction (2004). Core-periphery structure and systemic cycles.

- Streeck, Wolfgang — How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System (2016). Theory of capitalist decomposition and unmanageable crises.

- Polanyi, Karl — The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (1944). Analysis of fictitious commodities and the self-protection of society.

- Gramsci, Antonio — Selections from the Prison Notebooks (1971). Concepts of hegemony, crisis, and “interregnum.”

- Hudson, Michael — …and Forgive Them Their Debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year (2018). Synthesizes historical analysis of debt, oligarchy, and the political economy of social collapse, informing the text’s view of demographic pressures as a new frontier for rent extraction and systemic failure.

Want to stay informed about global economic

trends?

Subscribe to our newsletter for weekly analysis and insights

on international politics and economics.